Electric Mandolin

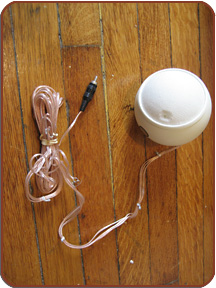

SensorBall |

By Sarah Manguso

Harris was one of my best friends.

He consoled me through ten years of bad relationships. I can’t tell you how many times he

cheered me up by reciting Alvy Singer’s line from the movie Annie Hall, when he asks a happy-

looking couple on the street, “What makes you so happy?” And then I’d say the woman’s

line, “Well, I’m very shallow and empty and I have no ideas and nothing interesting to say,” and

then Harris would say the man’s line, “And I’m exactly the same way.”

I believe that Harris was a musical genius, but one of his great virtues was his deep and generous

excitement about music. Over the past ten years, he brought me to see Roy Hargrove’s Big Band,

a Norwegian industrial group, a French Gypsy jazz trio, and free punk rock in Tompkins Square

Park—music I would not have known to go and find without Harris.

One year I had a piece of music in my head for months. I was pretty sure it was Bach, but I didn’t

know anything beyond that, and I remembered only the first few bars. After months of wondering

what they were I sang them to Harris—and he immediately said, “Oh. That’s the fugue to the

Bach G minor violin sonata.” And of course he was right.

In the year 2000, while Harris was composing music and, in his spare time, starting an internet

company, he commissioned a poem from me, assigned a subject and took me out to a fantastic

dinner as payment. He was that rarest of things: an artist who’s also a patron of the arts.

It started out as a joke, but the poem eventually wound up serving as the central part of my first

book. I’m going to read a poem from my second book, though, for Harris today, because it seems

more appropriate. It’s the last poem in the book, and it’s spoken by Oblivion.

Oblivion Speaks

I am not here to ruin you.

I am already in you.

I am the work you don’t do.

I am what you understand best and wordless.

I am with you in your chair and in your song.

I am what you avoid and what you stop avoiding.

I am what’s left when there is nothing left.

Love me hard, pilgrim.

By David Sollors

(Matt H. helped me with this, as did Audrey, Mark and Jenn)

When he was in the 9th grade, Harris was determined to have a solid-body electric mandolin. He had been playing the violin from an early age, and, as we all know, he excelled in his classical training. Somewhere along the way, maybe in his early teens, he also started playing mandolin, starting with an old instrument that belonged to his grandfather, who had been active in the Yiddish music scene on the Lower East Side. Since all of us here were witness to Harris’s musical prowess, I don’t have to tell you how quickly Harris mastered the new instrument. He strummed and tremelo’d with the best of them – quickly making his way through the mandolin repertoire, and finding a like-minded community, as well. He found bluegrass jams on Long Island, even joined the Long Island Mandolin Orchestra, of which he was the only member under 60.

After a while, though, he started feeling constrained by the limitations of a plain old acoustic mandolin. In short, Harris was a teenager who wanted to rock. Now, most kids would just get an electric guitar. But that’s the easy way. Harris represented the mandolin faction, and he wanted to rock out his way – with a solid-body, single-course, double-coil humbucker mandolin. There was only one problem: no such thing existed.

Again, someone else would have given up, would have seen the lack of a market for solid-bodied single course, double-coil humbucker’d mandolins as a reason to abandon his dream. But Harris was not deterred.

Now, I’ll take this opportunity to remind the younger folks in this crowd that when we were 14, the Internet as we know it did not exist – believe me, if it had, Harris would’ve known. Harris wanted to build an electric mandolin, and to find out how, he had to do it the old-fashioned way. He consulted with guitar-builders, pickup manufacturers, a guitar parts catalog, and our shop teacher. Harris bought a sheet of beautiful mahogany, traced an elegant pattern on it, and brought it to school to cut it during shop class. He routed out channels for the pickup and electronics, and mail ordered the tuning gears, the fretboard, and yes, the double-coil humbucking pickup and installed them all.

And ultimately, Harris got what he wanted – a solid-body, single-course, double-coil humbucker mandolin. A beautiful instrument, entirely of his own design. And again, everyone here is familiar enough with Harris that I don’t need to tell you what happened next – he rocked out. And I got to be there, because we played together in a band, inventively calling ourselves Harris n’ Dave.

And the reason I got to be in a band with Harris is because he taught me everything I know about music. After we’d been friends for a couple of years, he said to me – don’t just sit there, make yourself useful, learn how to play music!

Again, Harris saw a need, and he responded by building his own solution – in this case, me. I wasn’t a fine piece of mahogany, but I’d do.

I can hardly express my gratitude for the gift he gave me – scales, chords, harmony – he opened a whole new world to me. Before, there were just songs I liked. Afterwards, there were basslines! And minor chords! And choruses and bridges!

And of course, I’m not the only one whose life was enriched by Harris’s generosity, musical and otherwise. Harris n’ Dave, our folk duo, eventually turned into a twelve-piece combo with a brass section, a DJ and a female rapper. And after high school, he continued to do what he did at 14 – rock out. Many of you here played with him, in bands including

H-Bomb

Hypnotic Clambake (these names are all real, by the way)

Sweet Jeebus

Klezmerama

Metropolitan Klezmer and Isle of Klezbos (in which he was an honorary Klezbian)

the Pitfalls

King Willkie

the World on a String Band,

Object Collection

with Frank London and Roland Stebbins

Radu

STEVEN

Experimental Music Workshop

Deprivation Orchestra of NYC

Society of Automatic Music Notators

Chop Shop

The Seven Guys

The Berklee Bluegrass Boys

Sharqija

The History of Winter

Xtra Large

Makkataka

We’re seeing a theme here – Harris was never willing to settle for the world as it was – instead, he set out to create the world that he wanted. And not just as a musician. As a recent graduate music and computer science in New York’s new media scene, he was present at the creation of the online music phenomenon. He co-founded Upoc, a company that helps people connect. He developed his own software – and hardware – to help bring to life his innovative musical compositions.

And I would like to propose that he created – or helped create — the world in which Brooklyn bands are required to play bluegrass, klezmer or Balkan music in order to be cool. Because I’ll tell you, when we were playing it in high school, it was not cool, even if you had a handmade solid-body, single-course, double-coil humbucker mandolin.

And there’s his most important creation, his life’s work – the community that’s right here in this room. His family – Howard, Carol, Michelle, his cousins, aunts and uncles, friends, people from Great Neck South, Levels, Theater South, French Woods, Amherst, Silicon Alley, Chambers Street, Upoc, Brooklyn, Eastern Europe, CalArts, CUNY, Imaginova, and so many others. We are here because of Harris. We – this community of people who loved and admired him so much – we are the world that he created.

By Peg Mikkelsen

This is what it is like to be Harris’ friend (if the friend you are talking about is me).

You will meet him in a critical theory/political science class in which you will have no idea what neither he nor the professor is talking about, even though it is your major, not his.

He will agree to be in your show of solo performances. He will play Prince’s “Kiss” on mandolin. You will promptly fall for him.

(more than friends interlude in which Harris takes you to your first show at the Knitting Factory—The Mountain Goats—and teaches you how to cross a Manhattan street against the light. He will try to take you to the Jewish museum on a Saturday. He will keep an intimidating Walter Benjamin book by his bedside. He will hold you while you cry about your parents’ recent divorce. He will tell you you remind him of his father.)

He will email you when you are having a rough time studying abroad, just to check how you’re doing.

You will visit him on Chambers street, and he will take you to a cigar bar where you will pretend to know what you’re doing and he won’t let on that he knows you don’t know.

He will come to a party at your basement apartment shortly after your engagement where you will discuss marriage vows as speech-acts whose meaning lies partially in the fact that they are the exact same words other people say. Ergo, don’t write your own vows; they will be less meaningful, not more. You will not write your own vows.

He will share his George Jones double-CD set with your George Jones-loving fiance.

You will go live abroad, Harris will go live in California, and then, because the fates shine upon you, shortly after you both return to New York, you will be crossing 35th street at the same time in opposite directions. You will tell him you work for an anti-sexual violence organization and he will respond, “That’s great! I hate rape!.” Your organization will start selling “I hate rape” t-shirts. You will lunch at regular intervals. He will invite you to every show he has. You will complain, Harris will listen. Harris will complain about hair loss. You will tell him men shouldn’t worry about hair loss. He will ask what they should worry about. You will reply “penis size” and be rewarded with the bark of laughter someone else described so well. Making Harris laugh will be a new hobby, and you will try to think of funny things to say when you next see him. He will join you for karaoke when no one else can make it. He will let you buy him drinks, but repay you doubly with “Billie Jean” sung in the style of Johnny Cash. He will walk you home at 1am. You will not yet know he is a brown-belt in karate so you will be a little concerned that this man you nearly outweigh is your protection. He will tell you you are as pretty as you were in college even though you are clearly a cup-size smaller and a hip size larger. You will give him homemade chocolate sauce, which he will eat on English muffins. He will say nice things about your child. He will tell you he would like to be a parent. You will go to one of his experimental music performances where he will say that everyone else played better than he did. He will suggest having lunch at the 2nd Ave Deli during Passover. It will be closed. He will tell you how every year he considers whether or not to observe passover, and he always decides not to, but that the decision-making process is important anyway. He will talk about various traditions of religious erotic poetry. You will think that perhaps you should cancel your People magazine subscription.

He will die way too soon. You will cry until you can’t cry any more and then cry some more. You will look through all your things for the earrings he bought you, the guitar pick you stole, the voice message he left last. You will find a beautiful letter he wrote you on index cards enclosed with an annotated map of Eastern Europe (including what he called the “Klez Belt.”) And a tag from the “geological” candy he gave you (with each layer being a different kind of candy). And cheerful Facebook messages. And music. Thank god for that. How lucky you will be that your friend left behind something so beautiful, something that can be shared.

By Lukas Kendall

Hi All,

I wrote the following for the Amherst alumni magazine. I thought it would go in our class notes page but they used it as his obituary. I don’t want to say I was “glad”… those obits are always the first thing I read and to see Harris’s name there makes me want to cry…but I am pleased that people seem have appreciated the piece. Carol Wulfson asked if I could reprint it here and of course that is no problem:

I met Harris freshman year in music class and we grew closer over our time at Amherst, culminating in senior year when we had singles in Milliken sharing a bathroom. Living so close, I saw not only the kind of one-man carnival that he was with his bands, projects and friends—like living next to the beloved mad scientist—but during trying times as well: when he was obsessing over music projects (which always came out perfect) or frustrated over unrequited love.

It may surprise people to know that Harris had an intensely private core and would not talk about certain things even if you basically cornered him; he was so funny and charming that it let him hide, in a way, behind his wit. This may be a peculiar time for such an observation, but it’s important as context to how consistently kind Harris was despite his moods. As an artist, and a postmodernist one at that, he expressed himself not only through his music but his actions and words, which were consistently funny but never mean. I don’t remember him ever being rude to anyone; whatever dark thoughts he had in his head, maybe there would be a moment when they rattled around, but what came out of his mouth was funny, ironic and observant. That kind of contract with humanity can’t be taught or maybe even learned; it is intrinsic as well as rare.

Harris and I were a lot alike—ethnically, intellectually, even physically—but I remember thinking of him as the better man for the sweetness and warmth (but never sentimentality) of his personality. He was, in a word, gentle, and the contrast between this essential nature and the biting truth of his observations—which were so upbeat and ironic that they hid a melancholy that perhaps he didn’t understand himself, but is a hallmark of great art—had a magnetic pull upon all of us who knew him. His art, to which I always looked forward, was just like him: imaginative, playful and captivating. He was, himself, a kind of living artwork in one important way: if you knew him, even a little bit, it caused you to go places you never would have expected. Intellectually and emotionally, you ended up on a journey that was not only delightful, but meaningful and enriching—furthering you along in your connection with humanity. We, the audience, dearly loved him for it and are heartbroken to think of going on without him. I should add (he would appreciate this) that the act of writing these words will only distort the unknowable truth of who Harris actually was. Finally, my mind used to wander, and still does, that Harris and I would have had a lifelong love affair had we not had the mutual misfortune to be heterosexual. But as he would have surely agreed…nobody’s perfect.